Data model

Named graphs

Named graphs are typically used in RDF data modelling to provide additional context for RDF data; they are often used for timestamping, or to indicate the provenance of a triple. This means that as well as using triples (subject, predicate, object) for the data, we use quads (subject, predicate, object, context).

<graph> { <subject> property "value" . }

The identifier for a named graph can also be the subject of a triple; this is how we attach the metadata which describes the context represented by the named graph.

<graph> property "value"

How we use statements in BODS as named graphs - as a structure to provide context for a record - is explained [below](#statements-and-record-details.

Identifiers

Publishing beneficial ownership data as linked data requires generating globally unique identifiers (ideally HTTP URIs) for at least the core parts of the data model. These URIs serve as the subject in any RDF triple or the graph identifier in a quad.

In some cases, identifiers which are unique - but which are not HTTP URIs - may already exist.

The Beneficial Ownership Data Standard describes how to generate identifiers for statements, and explains how to derive identifiers for records. The RDF representation should retain these unchanged, but for added clarity about their expected values the recordId and statementId properties from the JSON representation are renamed recordIdString and statementIdString in the RDF vocabulary.

For certain components in the data model, HTTP URIs to represent equivalent common concepts (eg. countries) may already exist and be in use by third parties. Where possible, we will aim to reuse these identifiers. In some cases, it may be preferable to create and maintain our own set of URIs for codelist values instead.

Details about which approach is taken to identifiers for the different parts of the conceptual model are given in the respective sections of this document.

Statements and record details

In the BODS 0.4 data model, Statements are ideally suited to being used as named graphs. A Statement provides the context for the details published in a record - when and how the record’s details were collected and published. The meaning of data captured in a record changes depending on the Statement with which it is associated; eg. a Statement may carry a different meaning depending on the date it was published, the source which published it, or an attached annotation.

Statement identifiers can be used as the graph portion of a quad:

<ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Max" <ex:statement123> .

And also as the subject of triples in their own right:

bods:statementDate "2019-01-01T12:34:00"^^xsd:dateTime <ex:statement123> .

In this way, record details about which a particular Statement is made are grouped together into the same context, and information about that context is provided by the predicates attached to the Statement.

As a new Statement is published every time the details in a record are updated, the identifier for the record is reused across multiple Statements. This means we may end up with apparently conflicting information:

<ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Max" .

and

<ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Maxine" .

published at different times.

Examining these triples along with the graph they are part of - ie. using quads instead of triples - shows which is the most recent data.

<ex:statement123> a bods:NewRecordStatement .

<ex:statement123> bods:statementDate "2019-01-01T12:34:00"^^xsd:dateTime .

<ex:statement123> <ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Max" .

<ex:statement234> a bods:UpdatedRecordStatement .

<ex:statement234> bods:statementDate "2024-01-01T12:34:00"^^xsd:dateTime .

<ex:statement234> <ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Maxine" .

We can examine the change over time of a record’s details this way:

SELECT ?name ?date WHERE

{

GRAPH ?statement { <ex:personabc#subject> bods:name ?name } .

?statement bods:date ?date .

}

ORDER BY ?date

Or search only for the latest data:

SELECT ?name WHERE

{

GRAPH ?statement { <ex:personabc#subject> bods:name ?name } .

?statement bods:date ?date .

}

ORDER BY DESC(?date)

LIMIT 1

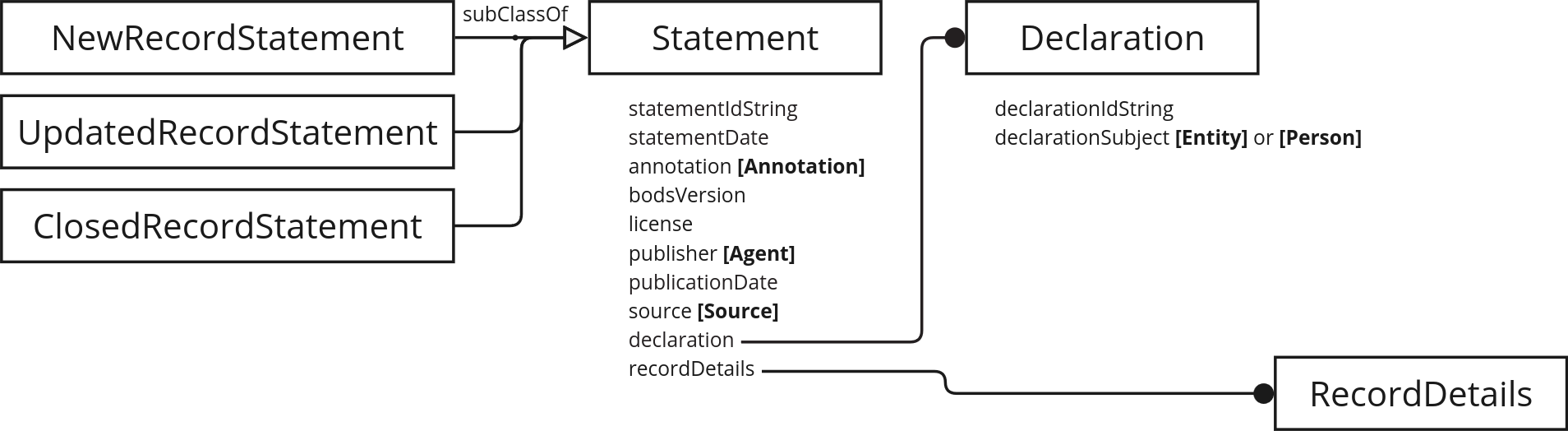

Statement types

The recordStatus property is replaced in the RDF data model by subclasses for the Statement class. Statements have an rdf:type value of NewRecordStatement, UpdatedRecordStatement or ClosedRecordStatement.

SELECT ?statement WHERE

{ ?statement a bods:NewRecordStatement . }

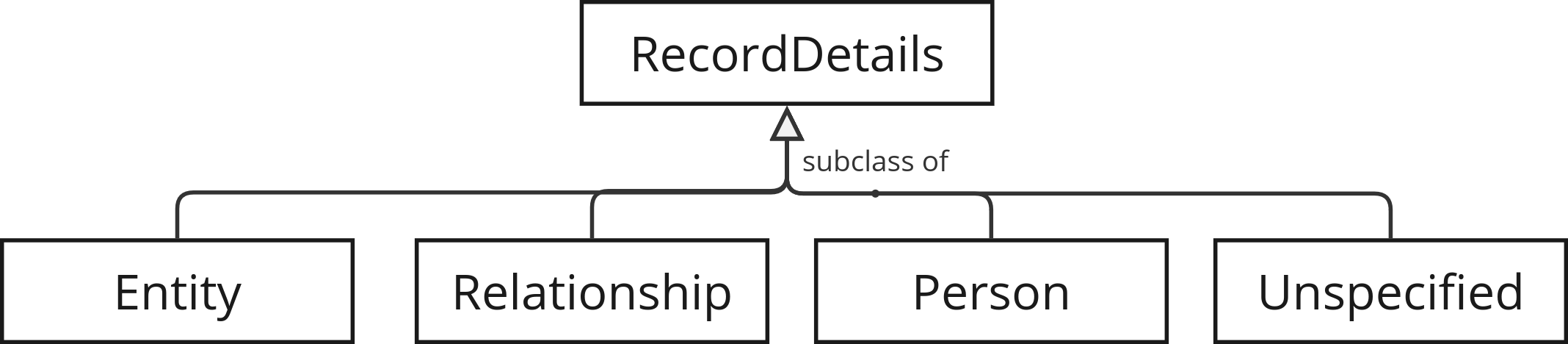

Record details

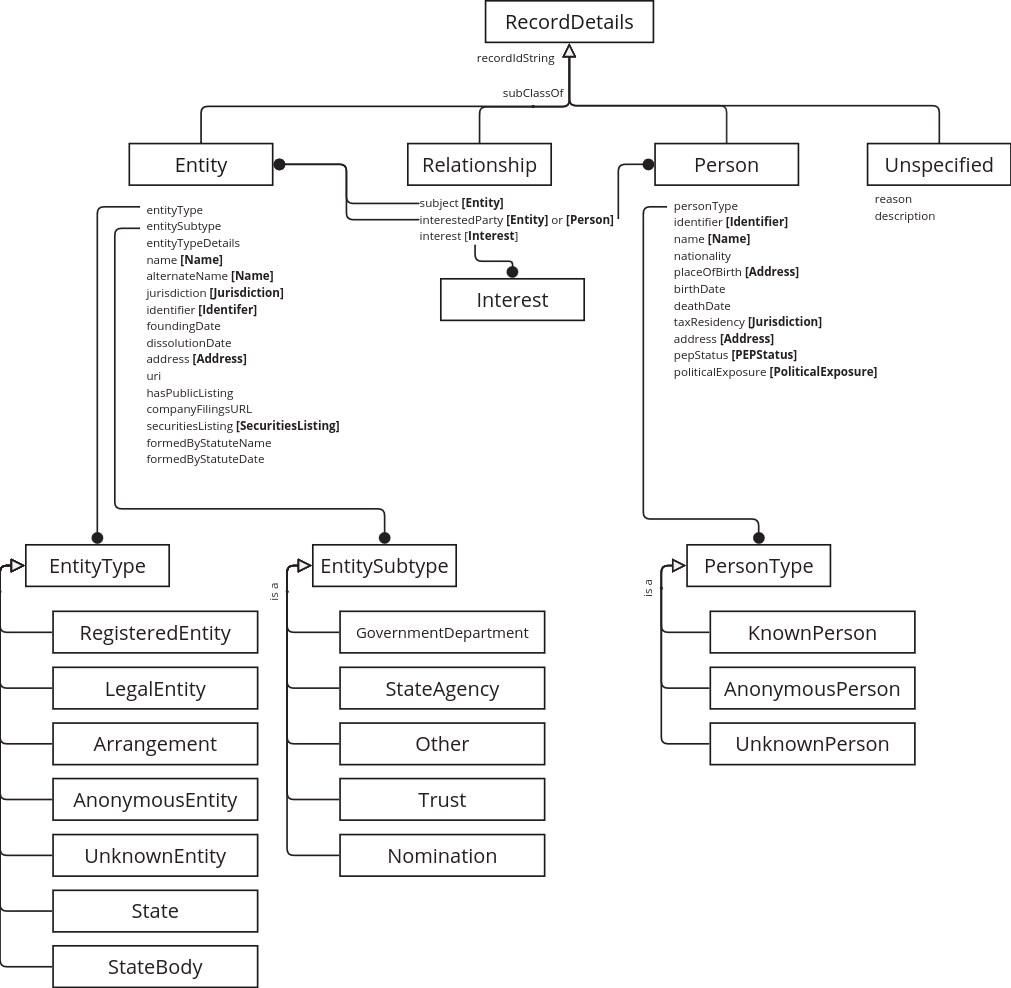

The BODS data model represents the details of records about people, entities, and the relationships between them. This is covered in the RDF vocabulary with the Person, Entity and Relationship classes, each of which are subtypes of the RecordDetails class.

While the GRAPH syntax can be used to find connections between Statements and the record details they reference when querying a datastore, we can also accommodate the “follow your nose” discovery mechanism by creating explicit links in both directions between instances of Statements and RecordDetails using the widely used primaryTopic and primaryTopicOf properties from the FOAF vocabulary.

<ex:statement123> foaf:primaryTopic <ex:record321> .

<ex:record321> foaf:primaryTopicOf <ex:statement123> .

For consistency with the JSON vocabulary we retain the recordDetails property, and define it as equivalent to foaf:primaryTopic. There is no equivalent to the inverse property in the JSON vocabulary.

Record identifiers

Record identifiers are expected to come from the information management system in which the record is stored (such as a companies register for a particular country). These identifiers are likely to be unique within the system, but not necessarily globally unique, and are unlikely to already be URIs. We can generate a globally unique URI for the RDF representation of the record from the recordId string and the org-id of the organisation which hosts the data, eg:

https://org-id.guide/list/GB-COH/record/c359f58d2977

This URI won’t resolve without a significant update to org-id.guide (which may be out of scope for org-id in any case) but for the purposes of querying the BODS data that doesn’t matter.

Declarations

Several claims about entities and the relationship(s) between them can be made at the same time. In BODS, this is represented by a Declaration which can link multiple Statements.

The only property defined in the JSON data model for a Declaration is declarationSubject, which is a pointer to the entity which the set of Statements is ultimately about. We consider this to be an equivalent property to foaf:primaryTopic in RDF. In the JSON representation of BODS this property belongs to a Statement object and has a plain string value; in RDF, the property belongs to the Declaration class, and the value is the URI of a RecordDetails instance.

Declaration identifiers

Similarly to records, declaration identifiers originate in a publisher’s system. The JSON representation of BODS uses the declaration property on a Statement to hold the string value for the external identifier. We replace this with a declarationIdString property on the Declaration class. The URI for a declaration can be generated from this string.

The declaration property is retained on Statement with a value of an instance of Declaration.

People, Entities and Relationships

The BODS conceptual model does not refer to people and entities (like companies) directly; it refers to data provided about them by a particular source at a particular time, detailed in a record. When records contain a unique global identifier for the referent (eg. via the uri property), this is still a claim being made, which may be contradicted by another source, or go out of date. We do not seek to associate data with an existing unique global identifier for a person or entity, nor do we generate our own identifiers for people or entities separately from the records about them.

In the RDF data model we introduce the RecordDetails class to represent the data held by a record in a data publisher’s system. All of the properties of a RecordDetails instance have a person, entity, or relationship as their conceptual subject; there is no data about the record itself. This means a RecordDetails instance effectively stands in for a Person, Entity or Relationship.

However, two different records from two different systems referring to the same person or entity are not equivalent, whereas two different references to the same person could be considered equivalent. Data from a record about a person may differ between records - eg. one record may have gaps where the other doesn’t - but this doesn’t mean we should infer that the records can be merged together.

The identifier for the instance, then, necessarily refers to the record. This also enables changes made to a record (which may or may not equate to changes to the subject!) to be tracked.

To align with the more conceptually “clean” approach generally taken in data modelling for linked data - which would require separate identifiers for the person/entity, and the record about them - but without deviating too much from the BODS conceptual model, we can append a # value to the end of the record identifier to refer to the person or entity which is the subject of that record. This means that we can say:

<ex:personabcd#subject> bods:name "Max" .

<ex:entitymno#subject> bods:name "Ball Co" .

<ex:relationshipxyz> bods:subject <ex:entitymno#subject> .

<ex:relationshipxyz> bods:interestedParty <ex:personabc#subject> .

And the semantic meaning of these statements is that the person has an interest in the entity (as opposed to the record about the person having an interest in the record about the entity) - without us needing to generate completely new identifiers for people and entities or additional infrastructure to resolve them.

The string that follows the the # character is arbitrary; it can be anything. We recommend to use the same string everywhere; eg. something like #subject or #id.

To generate the URI for a person, entity or relationship, we recommend using information available as part of the identifiers property if available, or generating random uuids if not.

Types and subtypes

The entity and person types and subtypes in the BODS conceptual model do not lend themselves to a class hierarchy in RDF, because a) the properties which are applicable to instances are the same regardless of the type/subtype, and b) all but one of the entity subtypes (trust, governmentDepartment, stateAgency, other) are used with more than one of the supertypes; it’s no use for inferencing - data would actually be lost. It also doesn’t make sense semantically, as the types and subtypes apply to the entity or person and not the record about them.

For this reason, we define instances of EntityType, EntitySubtype and PersonType as part of the vocabulary, to be used as the values of the entityType, entitySubtype and personType properties.

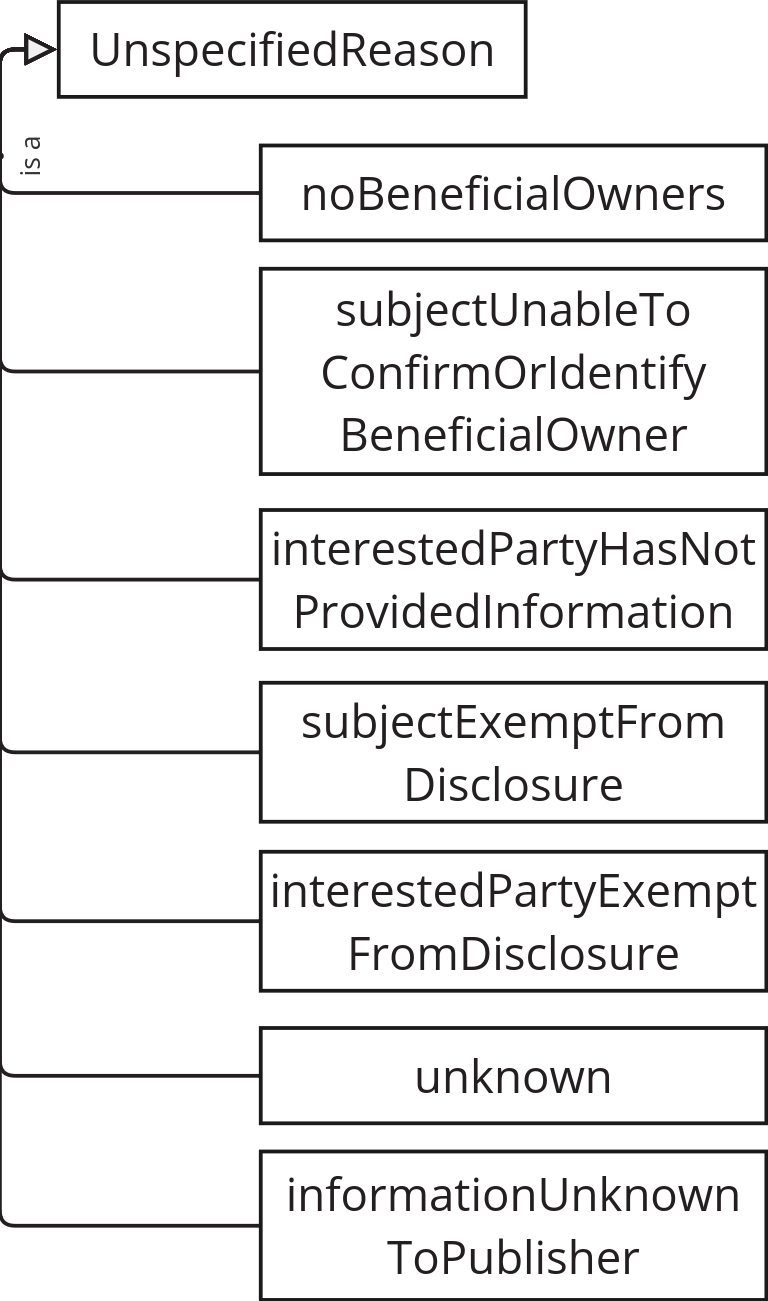

Unspecified record subjects

Missing or incomplete data is explicitly accounted for in BODS as there are many potential reasons for and implications thereof. This aligns well with the open world assumption which underpins data modelling in linked data.

In the JSON representation of BODS, missing data is described by a combination of a particular type value with additional requirements specified (eg. "personType": "anonymousPerson") and a nested object in the record details under one of the unspecifiedEntityDetails, unspecifiedPersonDetails, interestedParty or subject properties (depending on the record type). In the RDF data model, we replace this with the UnspecifiedRecord class, and define instances for each of the values of the unspecifiedReason codelist.

When partial data is known, an instance can have multiple types so that the necessary properties are available, eg.:

<ex:entitymno> a bods:Entity, bods:UnspecifiedRecord .

<ex:entitymno#subject> bods:entityType bods:UnknownEntity .

<ex:entitymno#subject> bods:jurisdiction codes:FR .

<ex:entitymno> bods:reason codes:informationUnknownToPublisher .

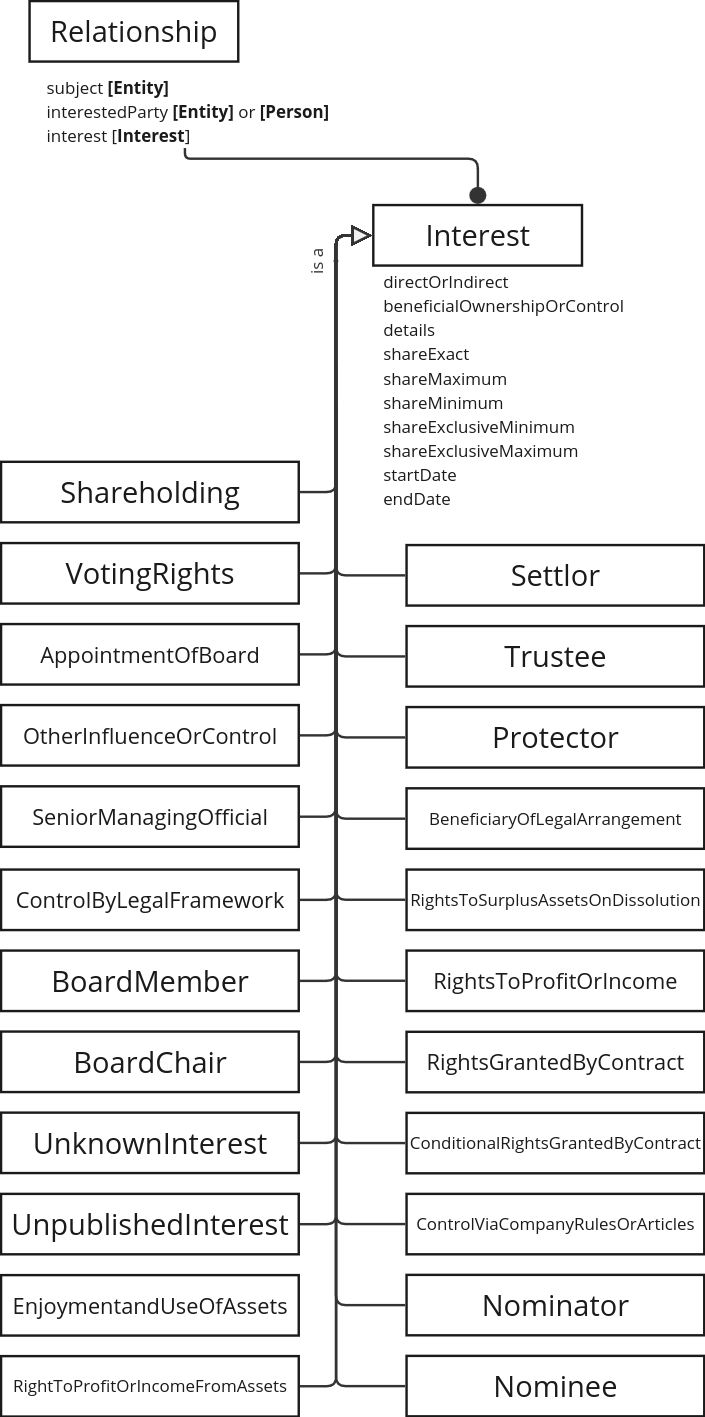

Interests

Multiple interests can be referenced from a single record about a Relationship, so each Interest needs to be instantiated in its own right. Interests are central to BODS; they are a distillation of external information from records which don’t directly map to an external artefact (like a specific record in a publisher’s system) and aren’t necessarily expected to have their own unique identifiers.

The BODS Interest Types codelist is used as a type hierarchy for Interest instances in the RDF data model. In a future version, the properties which are available to each type of Interest may be constrained as this becomes defined in the data standard.

When representing beneficial ownership relationships in RDF, we can either generate URIs for Interest instances or use blank nodes.

The main disadvantage of using blank nodes is that when combining linked data from different sources, identical interests won’t be automatically identified. However the same problem remains with URIs, unless a standard algorithm is agreed between publishers for generating them.

Any system which needs the data about an Interest to stand alone and be dereferencable should generate URIs for Interest instances. In most cases, the Interest data will only be useful alongside the Relationship of which it is a part and corresponding Statement (both of which have their own URIs), so in most cases using blank nodes will be adequate.

Other components

In this section we describe the ways in which the RDF representation differs from the JSON representation of the data model with regard to the rest of the object types and property names which make up the standard, and other considerations that need to be made when converting data to RDF.

Flattening nested objects

Nesting properties in JSON can make it easier to automatically traverse data, but treating every nested object as something to manifest as a separate instance in RDF can create an unnecessary level of complexity. To simplify the data model as much as possible, the following concepts which are presented as nested objects in JSON are flattened to become properties of their parent object in RDF:

Interest/share: all properties are available for an instance ofInterest.Statement/publicationDetails: all properties nested underpublicationDetailsare available for aStatement.Statement/recordDetails (entity)/entityType: is flattened into theentityType,entitySubtypeandentityTypeDetailsproperties onEntity.Statement/recordDetails (entity)/formedByStatute: nested properties are flattened toformedByStatuteNameandformedByStatuteDateonEntity.Statement/recordDetails (entity)/publicListing: nested properties are flattened tohasPublicListing,companyFilingsURLandsecuritiesListingonEntity.

Note: this is only possible when there is a one-to-one relationship between the parent and child objects.

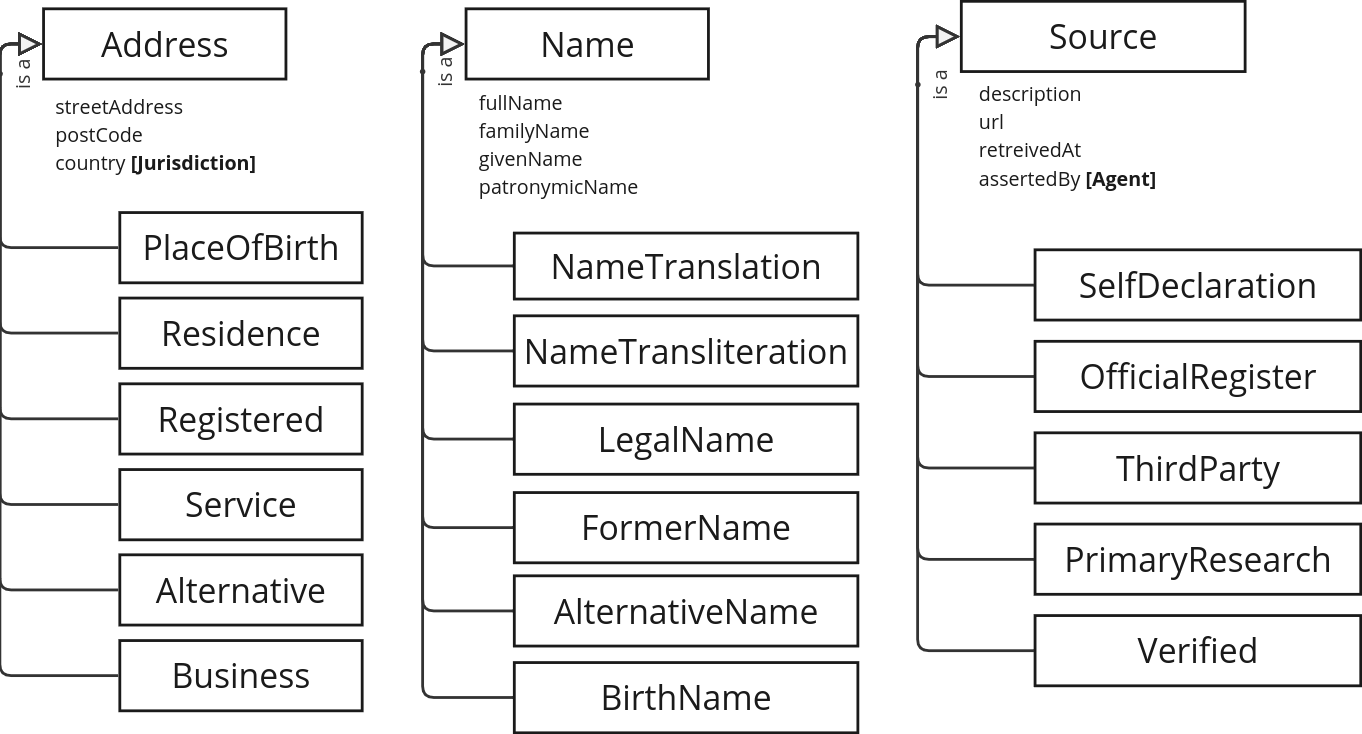

Class hierarchies

As well as those already mentioned, the following parts of the data standard are defined as classes with subclasses in the RDF vocabulary:

Address, with subclasses from theaddressTypecodelist.Name, with subclasses from thenameTypecodelist.Source, with subclasses from thesourceTypecodelist.

Instance definitions

Some parts of the data model are instances of a class for which we must define a URI so they can be consistently reused. For the most part, these come from codelists.

EntityType: each instance from theentityTypecodelistEntitySubtype: each instance from theentitySubtypecodelistPersonType: each instance from thepersonTypecodelistJurisdiction: each instance corresponding to an ISO 3166-1 or ISO 3166-2 definitionAnnotationMotivation: each instance corresponding to theannotationMotivationcodelistdirect,indirectandunknown: per thedirectOrIndirectcodelistisin,figi,cusipandcins: per the securities identifiers scheme codelistUnspecifiedReason: each instance from theunspecifiedReasoncodelist

Anonymous instances

When there is a one-to-many relationship between two objects (eg. a Statement can have multiple Sources), the properties cannot be flattened onto (what would in JSON be) the parent, but the instance in RDF needs to have its own identifier. In the following cases, there is little value in generating URIs, so blank nodes should be used:

AddressNameAnnotationSourceIdentifier(if no URI available)PoliticalExposureSecuritiesListing

Class and property names

For readability and consistency, all property names expressed as plural in the JSON representation (typically because their values are Arrays) are converted to singular in the RDF vocabulary.

type recurs in several places in the BODS data model, but is not used at all in RDF, preferring instead class hierarchies, or the entityType and personType properties.

ISSUE

As all properties in the RDF vocabulary are in the same “bucket”, ie. not segmented by the object to which they belong, some duplicate properties will need to be renamed, or to have their descriptions updated to accommodate multiple uses.

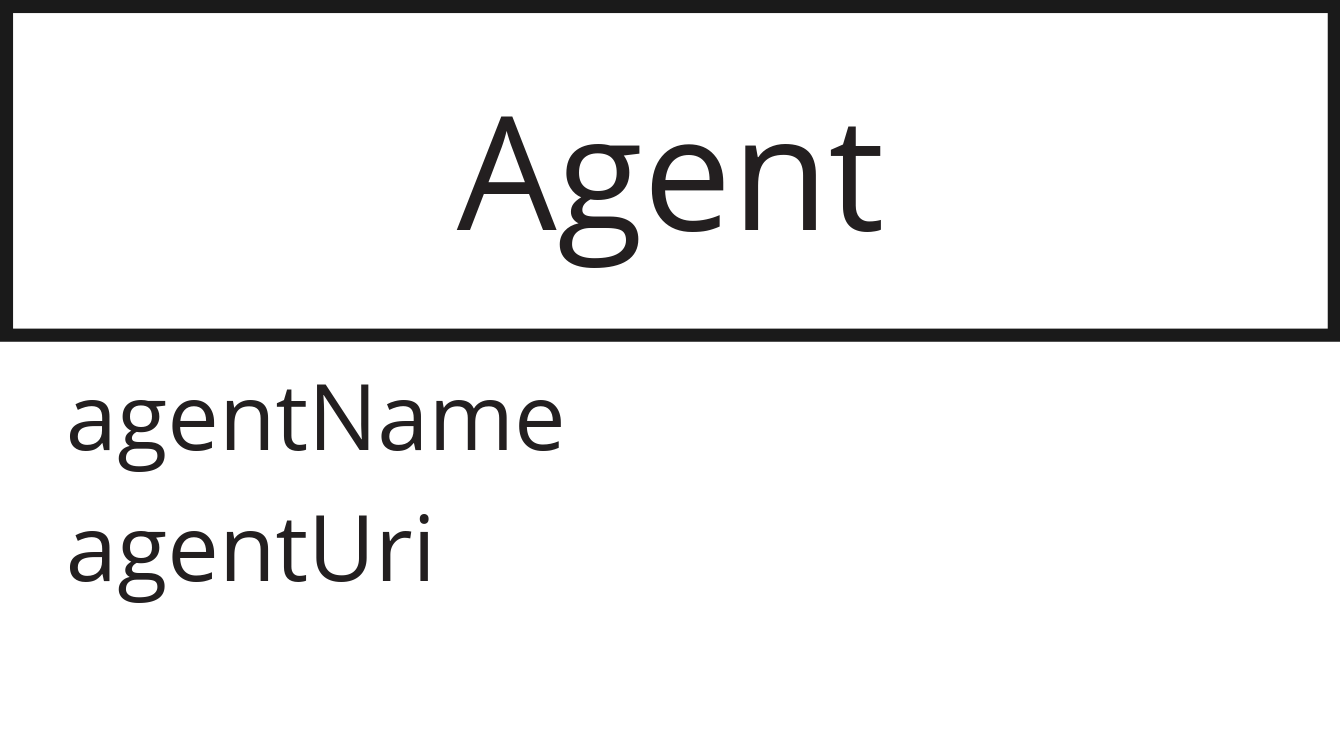

Aligning attribution properties

There are three places in the data standard where something is attributed simply to a name and URI, but where the implementation in the JSON representation differs slightly for each one:

Statement/publicationDetails/publisherAnnotation/createdBySource/assertedBy

We take the opportunity to align these in the RDF data model with an Agent class, an instance of which can be used as the value for each of these properties. In cases where an external URI is provided for the Agent, we can use this in our datastore as the identifier directly. In cases where this is missing, we should use a blank node (unless there is a compelling reason to generate a new URI of our own - for example, for a publisher providing lots of BODS data but without their own permanent identifier, or a source which recurs frequently).

This consistency could also be carried forward into future version of the JSON representation of the data model.

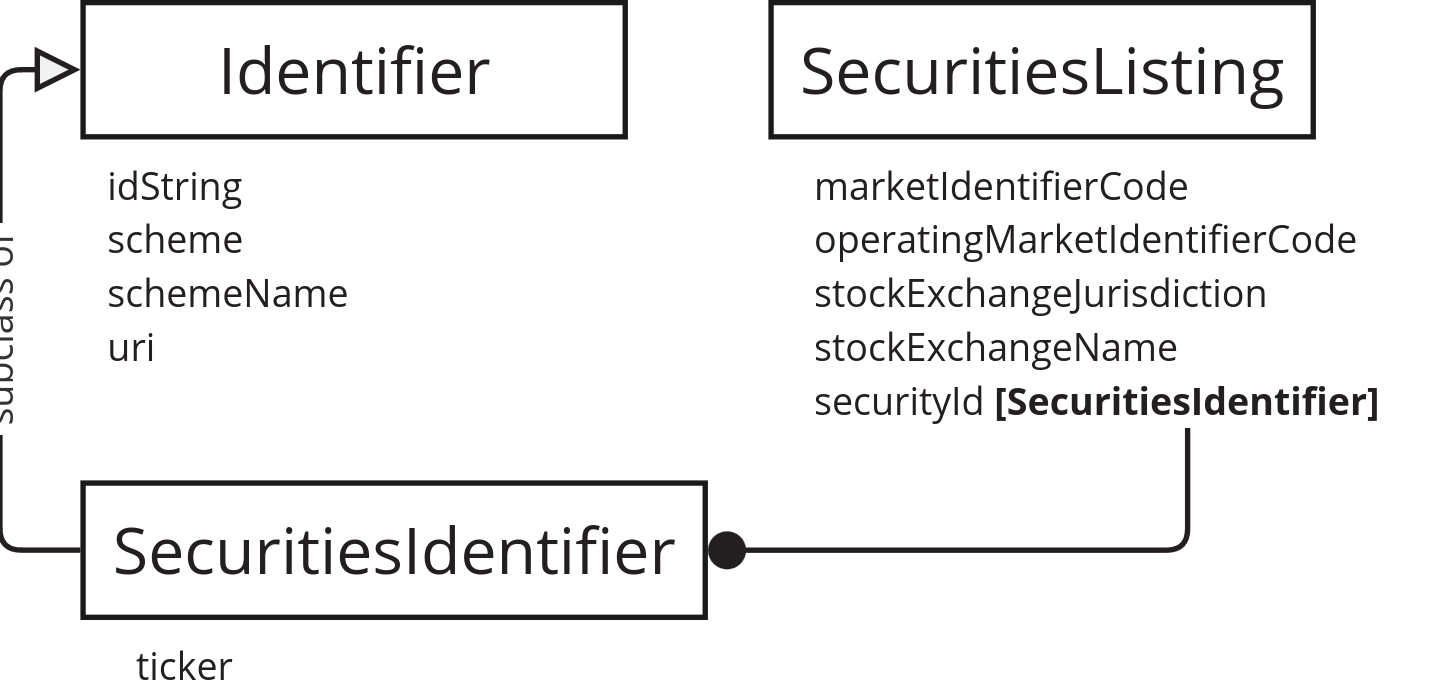

External identifiers

The Identifier object in BODS points to an external mechanism for uniquely identifying something. We keep the Identifier class, and to reduce confusion with standard RDF terminology, we make the following changes to its use:

- If a value for

uriis present, treat this as the URI for theIdentifierinstance. - Rename the

idpropertyidString.

And we update SecuritiesListing/security as follows:

SecuritiesIdentifieris a new class, subclass ofIdentifier, with the additional property ofticker.- The property

SecuritiesListing/securitywith a nested object as its value is replaced by the propertysecurityId, the value of which is an instance ofSecuritiesIdentifier.

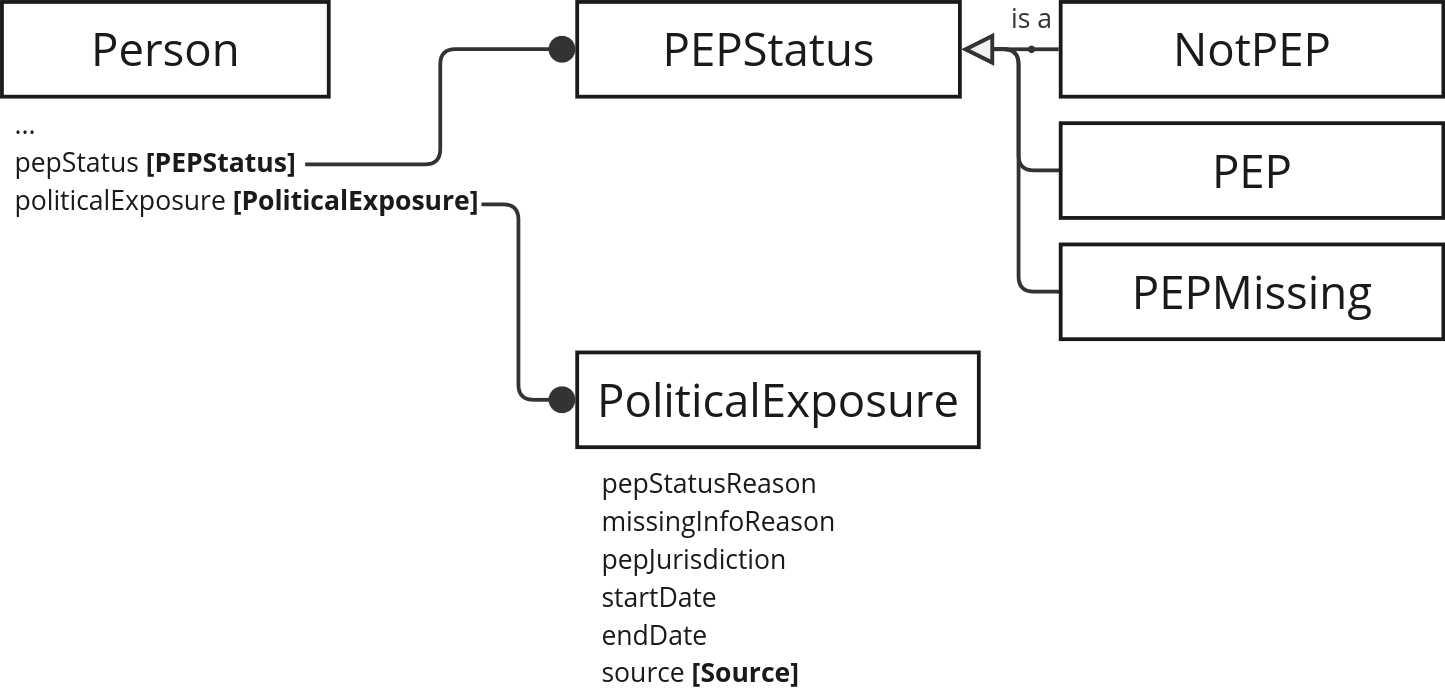

Political exposure

In the JSON representation, there are multiple levels of nested object to describe the political exposure status of a person, and multiple sets of details can be included. For the RDF vocabulary, we make the following changes:

- Create a new

PoliticalExposureclass; an instance of this holds the properties of thePerson/politicalExposure/detailsobject. - Replace

politicalExposure/statuswith apepStatusproperty onPerson. - Create a new

PEPStatusclass and define the following instances:NotPEPPEPPEPMissing

Instances of PoliticalExposure are identified using blank nodes.

Locations

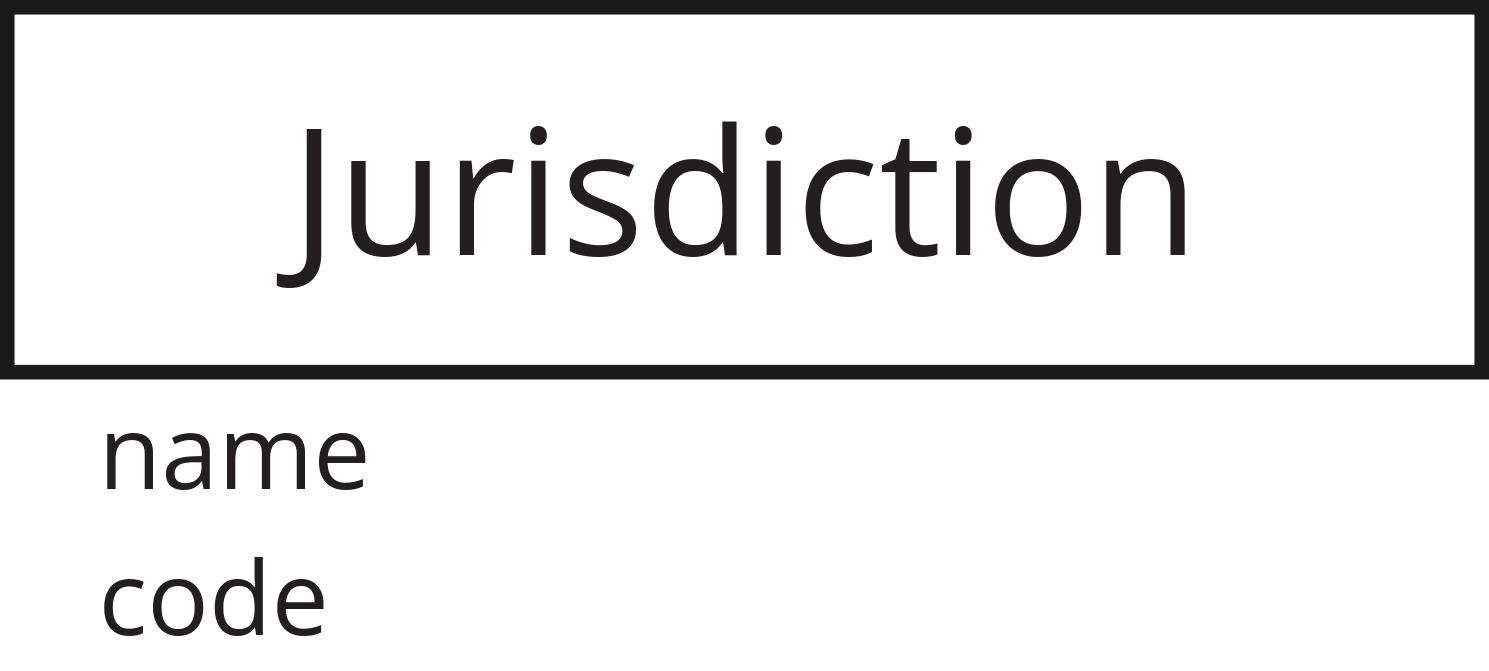

As Country is a type of Jurisdiction, we remove Country from the RDF vocabulary, define Jurisdiction as a class with properties name and code, and use this in place of Country throughout.

There is no consistent, reliable source of external URIs for jurisdictions in line with ISO 3166-1/2 so we recommend defining URIs as part of the BODS vocabulary to refer to for values of the Entity/jurisdiction, Person/taxResidency and Address/country properties.

Direct and indirect relationships

The properties isComponent and componentRecords are not carried through to the RDF data model. We can traverse the graph to find the indirect relationship from a series of direct ones as follows.

TODO

Example SPARQL needed